The knurled cloth handles of Nicos’ hamper cut into his right hand. The straps are connected all the way to the base of the bag and the weight of the laundry keeps pushing them apart. They’re too short, now that the laundry is folded and holding the bag to its shape. You switch hands but there isn’t enough time to rub the indentations out of the left hand before the pain in the right hand is impossible.

Nicos puts the hamper down on a bench facing the front window of a coffee shop. People sit looking out onto the street—at the sidewalk and the bench and the parked cars and the road and the storefronts across the road that you can’t make out what they are from here. You have to rub your hands with each other and look out as well. How does anyone sit on this bench with the coffee shop staring them in the face. You’d have to seem surprised all the time that you’d caught someone sipping or biting or reading.

You can’t sit next to your laundry on a bench. It looks like you’re waiting for someone to come help you, because people can’t tell it’s done. Is it still laundry when it’s done, and folded. It’s laundry when it’s dirty, and while it’s getting clean, and while you fold it. It’s clothes when you put it away. You can sit next to clothes. Clothes are like shopping.

Nicos had sat next to half his laundry at the laundromat. Only because all the machines were full. You can sit next to your laundry in the laundromat, if the machines are full and you have enough for a good-size load. And if it’s a clean laundromat. How do laundromats get dirty. Car washes get dirty and the dirty ones have the strongest sprayers so you go to the dirtiest ones. Luckily the closest car wash is filthy.

You don’t care about how a hamper carries when the machines are in the building. Or when the laundromat at the corner is clean. Who sends you to a dirty laundromat. There isn’t another laundromat between here and home, so you have to buy another new hamper. The store that sells hampers isn’t on the way either.

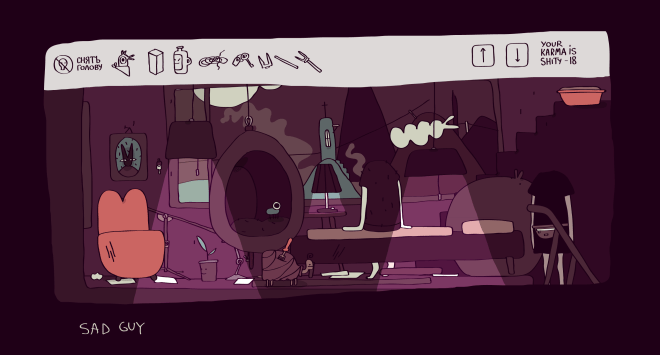

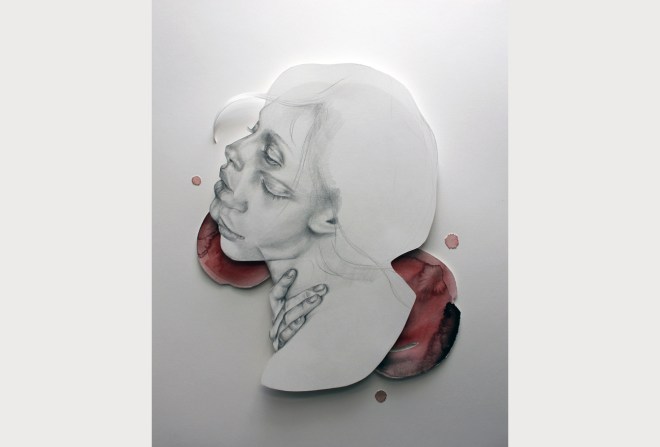

these words by Ajay Mehra were inspired by

the art of Pasha Bumazhniy

You must be logged in to post a comment.