When I was a child, my father would rake leaves in the front yard and when the pile was big enough, he’d pick me up and throw me (almost callously) into them. My father was wild in his younger days; he rode a motorcycle and played bass in an underground funk band. He settled down though, when he married my mother. He had a daughter, and found work as a cashier in a record store of dubious structural integrity but impeccable cultural acumen.

He killed himself when he was sixty-one.

***

There’s something slyly atavistic about the way the leaves, dried out now since they’ve fallen, feel against my hands as I rustle them gently. From behind the mountain, a small line of smoke stretches thin across the setting sun. Smoke signals at sunset, he says.

We’re quiet after that, for a long time. Uma Thurman had it right; you know you’ve found someone really special when you can just shut the fuck up and sit comfortably in silence, if only for a minute. Silence is a rare thing, and people don’t bother to make time for it anymore. How could they? There’s too many distractions, too many addictions. Screens everywhere, and sitcoms and internet dating websites, reality TV shows and political debate shows and the horrid, overwhelming cascade of contemporary pop music. There’s education and employment, no alternatives, and you’re left to choose between an outdated, meritocratic institution or the dreaded 9-5, an existence that’s so alarmingly mundane it’s turned an entire generation into alcoholics, assholes who waste their weekends on outrageously priced booze and horrific hangovers so as to forget that they owe their time, their lives, to companies who speak only in terms of profit. There’s internet pornography, advertisements and an endless supply of empty entertainment, assailing our senses and undermining our character, our concentration and our connections.

It’s all a joke, a joke with a vicious punch line that relies on the inherent irony of a situation whereby the most connected civilization in the history of humanity is destined to die alone, each and every one of us connected to the internet and nothing else. Where in this hilarious chaos can one be expected to sit and think on the endless potential of the universe, or even the endless potential of the self? I look again to the man beside me, and I tell him I’m afraid that not even the autumn leaves can save me from my vices, from my addictions both good and evil.

Don’t worry, he says. We’ll take refuge in the wilderness.

Don’t worry, he says. Once you’re unplugged, everything will be alright.

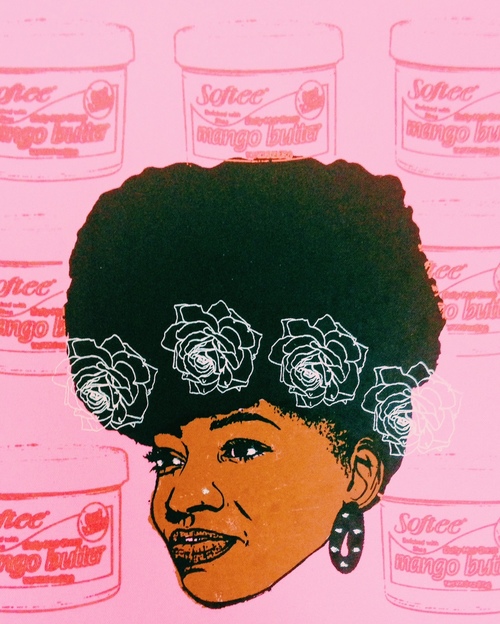

these words by Josh Elyea were inspired by the work of Daphne Boyer

You must be logged in to post a comment.