these words by Khatira Mahdavi were inspired by the work of Angela Pilgrim

these words by Khatira Mahdavi were inspired by the work of Angela Pilgrim

‘See you later,’

I say to you

as I leave you for the last time.

I do not know it yet, but when I return

our pool will be dry.

There will be no evidence

of our glorious summer days

soaking in the sun;

nor remnants of our gin-soaked laughter,

as we trudge through the snow in the winter.

You are gone; I wish I were.

I see telephone lines as they reach through the countryside,

searching for you,

and I feel your voice vibrate through your body,

while I rest my head on your chest.

I see the curve of an arch,

and I remember how miraculously our bodies fit together.

these words by Jess Goldson were inspired by the work of Mairi Timoney

Foreign

construction;

Mirrors

cling to past images,

Smooth

edges recite falsehoods

Fraught

with mixed emotions.

Dissociated

desire;

Fractured by efforts to complement the landscape.

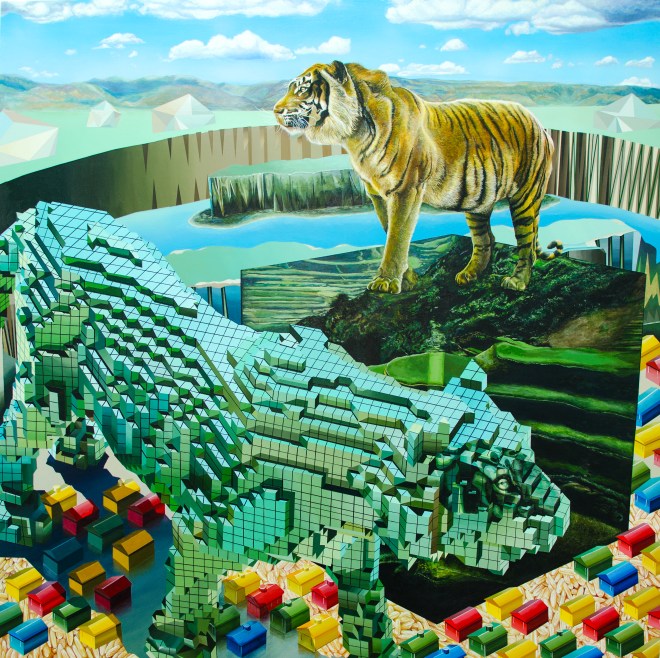

this poem by Jessica Goldson was inspired by Juan Travieso’s “The Monument”

This article contains references to a variety of forms of abuse.

I do not have the privilege to consider discussions of violence as intriguing places to display my intellect. I do not have the privilege to enter these talks as though it’s a game, to ‘play’ and say things in the tone of a dramatized television series politician before leaving the ideas behind when I exit the arena.

Instead I teach and I speak and I read and I write and I talk and I laugh and my body is still injured by the lazy romanticizations of violence from people who consider it meaningful because of its perceived deviance and sense of foreignness from their experiences, like the teenage boy who thinks he will become a man the first time he has sex. I am patient and I learn and I speak to paid listeners and I meditate and I fight and I exercise and I control addictions to substances or work or hobbies or people and I am still haunted by ghosts and still I react to conflicts in public that others have the luxury to laugh off.

Look at the people around you. Whether you are on the bus or at work or in line or in class or at the gym or in a library or in a grocery store or on the sidewalk many of the people around you do not have the luxury to ponder the presence of violence because they are hurt, trying to heal, about to be attacked again.

I often see groups of people who have not been injured ruminating among themselves over how violence feels or should feel or if it exists at all. Never do these talkers consider to ask the person with the snapped rib if their pain feels real. The argument seems instead that it is impossible to break a bone if the person speaking has not had their bones broken.

Whole cities, planets, must not exist to these people.

Survivors of violence do not have the luxury to engage in such conversations about the illusory nature or impact of violence because we are busy tearing off band-aids and pouring peroxide over wounds or wincing as wrists are pulled and re-broken. We do not consider to ask one another for proof because we have seen the x-rays.

Right now, you likely can’t tell which person around you is surviving violence because we have learned that hiding the tangible evidence of the faults for those who have attacked us is more important than our well-being. Complicated by the fact that Canadian society prefers to punish those who have been attacked than to address those who attack others, we blend. Because so much violence is also not as tangible as a bruise, hiding it is easier than you might think.

While many of these survivors around you listen to the opinions of those who have not been hurt about the proper ways to heal, know they do not take them seriously when they choose to philosophize about the existence or impact of violence. Let’s say a few volleyball players who have never played hockey suggest that hockey should be banned from television because it is too violent. In the least, they suggest, remove all checking from the sport. As a hockey player, how seriously do you take their opinion?

“I often see groups of people who have not been injured ruminating among themselves over how violence feels or should feel or if it exists. Never do these talkers consider to ask the person with the snapped rib if their pain feels real.”

1. The first glaring flaw of the anti-trigger warning speaker is that they believe their opinion to be binding. How seriously do surgeons take the advice of people who have never studied medicine?

2. The weakest and least creative arguments use violence as seasoning. Ask a survivor how much violence improved or ‘exoticized’ their life. How appreciative they were for the growth provided by the experience. The impulse to use trauma tourism as an attempt to expand the perceived depth of one’s personality or work is a mistake. Put in the work or do not touch the subject.

3. The laziest flaw of anti-trigger warnings is a confused connection to censorship. This is the volleyball player who, when a goalie asks for a helmet, suggests that goalies should not wear helmets because they won’t play if they wear them. Besides ignoring the request, this reaction is based on a bizarre logic and seems inspired by a fear of complexity, more designed to rationalize intellectual laziness than to resolve an urgent problem.

“A few volleyball players who have never played hockey suggest that hockey should be banned from television because it is too violent. In the least, they suggest, ban checking from the sport. How seriously do you take their opinion?”

4. The thin foundation of anti-trigger warning advocates is the suggestion that it is possible to speak about a topic without being political. That language has the capacity to be objective-as though omission and history and socialization are separable from experience as a socialized person speaking a language. This is particularly embarrassing to hear when the people are speaking English. Ask nations across the world how they came to learn this language.

5. The person without a history of violence who resists trigger warnings suggests that the bodies around them do not matter as much as the protection of their isolated beliefs. Neurologists have demonstrated that memory of pain and language registers in the same part of the brain as does immediate physical pain.

The last objective of any serious critical discussion should the impossible attempt to exempt ourselves from complicity through passionate defenses of laziness in order to avoid fixing a critical problem. Passive inaction is required for many forms of violence to continue. Don’t be an accessory to murder because your ego was too threatened to adapt.

To the anti-trigger warning camp: grow out of the lazy philosophical presumptions of being able to speak for ‘all’ and ask how to become the accomplices of survivors in your classrooms, in your workplaces, in your romantic relationships, and among your friends, who may not have felt comfortable sharing their history of trauma with you. If they don’t want to talk about it, don’t probe. If they do, help them to destroy the insecure ways of socializing people that has normalized and required violence to exact legitimacy (see: mass incarceration; we’re legitimate because we attacked ______ to keep you safe). This philosophy of power has trickled into the structures of our social relationships.

These models of social power relations are outdated and will be crushed. What side will you be on when they are history? The side furiously suggesting that they were not affected by words? Or the side that acknowledged the humanity of those around them and who worked to dismantle the violence that they internalized, from where their luxuries were drawn?

“The last objective of any serious discussion should be the impossible attempt to exempt ourselves from complicity through passionate defenses of laziness in order to avoid resolving a critical problem.”

I want to conclude with a complication of the “survivors” I’ve been using in this piece. I am referring to survivors of violence. I am a ‘survivor’ of child abuse. I do not aim to speak on behalf of all child abuse survivors. We are nuanced. The last time I checked, for example, a cousin of mine was abusing women in the way that he was abused by a woman as a child. I would likely be doing the same should I have lived through his exact conditions because conditions are largely responsible for the development of abusive behaviours (to avoid pain). I fail and I have failed others and I continue to fail for a variety of other attacked groups. Accepting the imperfections of my attempts because of my status as a nuanced human being seems vital to moving forward, toward healthier and less-violent ways of organizing and relating to each other. Protecting self-assessed conceptions of my illusory perfection through passionate defenses of laziness does not.

If you are unable to move past the guilt, and you are not a person dealing with trauma, know that we do not take your tantrums on violence seriously. You may threaten us. You may even attack us. Know that these reactions prove that our society relies on violence when it does not want to do the work of fixing a complex problem. Aligning yourself with passionate laziness is a bad look. Engaging with complex issues requires patience, and we are ready for you to learn how to be an accomplice and join us in the fight. Know that we will also be complete without it.*

The colour, “bla bla bla,” was provided by illustrator Marie Mainguy, who does not necessarily endorse the opinions of the author

Recommended works that continue this discussion

Video:

Siede, Caroline.”Sarah Silverman Sides with College Students in the Great PC War,”A.V. Club, 16 Sept 2015.

What’s The Deal With Trigger Warnings?, PBS Idea Channel, 16 Sept 2015.

Text:

Ahmed, Sara. “Against Students,” The New Inquiry, 29 June 2015.

Carter, Angela. “Teaching with Trauma: Trigger Warnings, Feminism, and Disability Pedagogy,” Disability Studies, (35), 2, 2015.

Livingston, Kathleen Ann Livingston. “On Rage, Shame, ‘Realness,’ and Accountability to Survivors,” Harlot, (2), 2014.

Mate, Gabor. List of articles

Mate, Gabor. In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts, Vintage Canada, 2009.

This is the memory: the grandfather sits in a chair in the kitchen, accordion on knee. He shuts his eyes and squeezes the instrument. A foot makes a beat. A crescendo fills the room, reaching for a climax that is always somewhere else. The floors shutter, the foot beats wilder. It is a miracle the chair does not break, that pictures do not fall from their hooks. Around the kitchen people dance and sway and laugh drunken laughs as the old man’s fingers dance an automatic dance upon the keys.

But in the grandson’s memory there is no music. Only a wheezing of air: the accordion desperate for breath, a gasping animal in his grandfather’s hands. Because he can never remember the music, he wonders if his grandfather ever really played the instrument—but the details are clear: the way the floor shook, the way the old man raised his knee, and the way he squeezed his eyes so tight that the unheard music became a thing extracted from the instrument’s wood, leather, and metal. Like a splinter squeezed from a finger. It is the very lucidity of the image that makes him doubt his recollection.

But that is the memory and this day is the present. And on this day the accordion rests next to the deep freeze, already aware of its ascent into that magical category of things-once-owned-by-people-now-dead. This day: two days after the grandfather’s death. The same house, located at the end of Vicky’s Close, named by the grandfather in memory of his mother. The dead remembering the dead.

The grandmother sits in the kitchen and the shadows of people enter and depart, wishing her well, bringing her food, offering condolences like cheese on a platter. She clutches a cane with knobby hands. She is 92 and she will be dead in eight months. She is thinking about the price of bread at the Co-Op, the way shadows have their own moods, and how violent men seem to love their mothers so.

And the grandson thinks about how violence expresses itself in the most mundane of actions. He thinks of how when he was young he sat in the chestnut tree outside and watched his grandfather close the curtains and turn all the taps on so that from outside the house rumbled with the gushing of water through pipes, concealing the echoing thud of belt against skin, a sound innocently mistaken for the swatting of flies. Later he will associate running faucets and the shadows of mid-afternoon with his grandmother’s bloodshot eyes and tension-stooped back. Blood and screams and broken bodies are banal compared to a tap left running, to an elongation of shadow on a kitchen floor.

The grandmother stares at the accordion and at the grandson and they both wonder if any music ever came from that instrument or if it really was just a wheezing, gasping bag all along. She thinks about a previous self, one vaguely resembling her own, and a black pit of seven decades opens up between that self and this one. She gasps and her face crumples and this loss of control lasts for two and a half seconds, but it is long enough for the shadows to notice. They think she is missing him and they offer more embraces.

‘Open the curtains,’ she says, ‘It’s a shame to waste such light.’

these words by Michael Warford were inspired by the colour of Teodoru Badiu

TW: self-harm, suicide

R: Ok. So, you need to talk to them about your mental illness, right?

Finn: Basically yeah, but I don’t know how. I keep starting but none of it feels right.

D: If you wrote more often, maybe you wouldn’t have that problem.

Finn: I — I know.

R: Well, what do you have so far?

Finn: I started with what I did when I was eleven…

[D scoffs]

[Enter A and SC. Both sit. A fidgets. SC smiles sheepishly and rubs A’s back.]

R: It’s okay. You need to start somewhere, right?

[SC whispers inaudibly]

Finn: Ok.

I closed my eyes, held my breath, and submerged myself in the water. It always looked a little gray in the tub. My weak limbs wallowed in the sway. One hand pinched my nostrils closed and the other floated somewhere around my stomach. I stayed this way, swaying, until the pressure pushing against my clavicle and filling my head began to pulse. Each time, I tried to hold it a little longer, savouring the feeling of expanding nothingness as long as possible, before my bodily instincts overrode my desires and I emerged, gasping.

I was 11. I didn’t know what ‘suicide’ meant.

No one ever knew about my bath time game —

A: Are you… are you sure you want to share that? If you tell them about that, they might think you’re weird. Or that you’re making it up. Or that you’re like really messed up. I don’t know. Maybe there’s a better way.

Finn: I know. You already told me that. That’s part of why I stopped.

A: What?! Oh no! You can’t stop! If you stop, you’ll never get it done!

D: Why does Finn not finishing something come as a shock to you?

A: Ok but they have to. They said they would.

R: Ok. Calm down folks. If we devolve into the two of you tugging at each arm again, they’ll never get anything done.

SC: [quietly] Finn, you should listen to R.

Finn: Ok. I’m trying. I promise I’m trying.

SC: I know you are. You’re doing great. I really liked your story.

Finn: Oh. Thanks.

D: I mean, you could have started the story at an even earlier place.

A: No. I don’t want to talk about THAT.

R: I agree with A on this one. I think that story will make a lot of people uncomfortable.

SC: I think Finn can talk about that if they want to but they don’t have to, either.

Finn: Maybe later.

R: Did you have anything to add to what you were saying earlier?

Finn: I mean, I guess. Not really, though.

R: What about what happened the fall before last?

Finn: Yeah. I guess I could start there. It’s kind of a blur, though. I can’t necessarily think of a particular event.

SC: That’s ok. You’ll find one as you go.

Finn: Ok. I guess it started in September. 22 going on 23. I guess by 22 going on 23, I’d accepted my lot, I’d accepted that these damn pills would never work and I’d never really amount to much — just like she said.

A: Please don’t talk about her.

D: Why? She was right.

R: Finn, just keep going.

[SC nods]

Finn: Ok.

It was barely September when the depression started hitting a little harder than usual. The echoes of summer heat reverberated through the window and made me sick. My eyes never quite opened before I dragged myself to the shower. I told myself it was only the newness, the change, moving out, getting used to graduate-level seminars and work. I took my useless pills to ward off the buzzies, the little electric shockwaves running from nerve to nerve when your system hadn’t gotten its juice, and dragged on.

Never take Paxil.

Never Take Paxil.

Never

Take

Paxil

I joined the editing team of a graduate creative journal. I was working as a teaching assistant. I had a research assistantship. Things were okay. I was busy — overworked, maybe — but nothing unexpected for a graduate student.

The exhaustion, however, only got worse. Periods of being suicidal. Waking up wishing I hadn’t. Feeling heavy in a foreign body. The slight relief of vertigo when getting up too fast. Resigning myself to draping my limbs over the side of the bed, letting my weight slowly slip me onto the floor, plopping into a contorted heap. All of these were normal when they took up a couple days here and there every few weeks amidst the lull of monotony, the drag of being. Slowly and all at once, creeping just enough to go unnoticed, a few days became a week, became a month, became my existence. The depression whispered to me that it was my own fault, that I just couldn’t keep up because I wasn’t enough. It almost replaced the voice that had been my mother’s — but this time I couldn’t barricade the doors, couldn’t turn up the music until she removed the fuse. It wasn’t until December that I noticed anything was wrong.

“Hey, boo. I think you should get up now,” Joon coos, sitting at the edge of the bed.

There is a day’s worth of sleep in my eyes; I barely pry them open, groan “hhhhnn.”

They try to smile, curling their lips in and pressing them tight. The pity pools in their eyes and pushes their eyebrows upwards. “Come on, I’ll make you tea.” I bury my face in their hip. One Earl Grey later, I stare out the window. Late afternoon and the day is already dimming. I have work to do. So much work to do. Heartbeat in head, shaking in chest, I am still, I am still, I am still.

Joon, too, is ill. They can’t keep taking care of me and I can’t take care of them. We lack clean dishes. Our only contact is with our pets and the ever-multiplying fruit flies in the kitchen. All our clothes are laundry. Floors no longer exist. I was supposed to have myself together. Not this. One more pill. Tiny oval in my palm. You were supposed to make it better.

They’ve made me worse. I spend a month trying to convince myself to make a doctor’s appointment. My mother’s voice in my head: you’ve cancelled too many appointments. I bet he won’t even see you now. It’s embarrassing.

Too many times. Embarrassing. Phone calls. Can’t.

I don’t make an appointment. I’m going to have to wean myself off these things on my own (always on my own) but I can’t yet. I’m mid-semester and already struggling. A decade of depression has made me a master of deception, bullshitting that I’ve read the things I haven’t. This and natural wit get me through seminar and class each week, and necessity keeps me from skipping them — though a handful, inevitably, are still missed. I slog through spring finals, spring corrections, and I start the weaning process.

R: What was the withdrawal like?

Finn: Hell. You become a different person. At first, it just feels the same as those days where you forget a pill. You think ‘Ok. Buzzies. Dizziness. Anger. Expected,’ but that’s just the beginning.

I started to cut down my dosage in May and the process lasted until the middle of July. What no doctor told me, what I found out through a series of blogs and forums, was that Paxil has some of the worst withdrawal. Heck, it’s been almost a year and sometimes I still find myself wondering if certain behaviors are the residue of my time with Paxil.

That first day in May, I sat down with a steak knife and cut several of my 30 mg Paxil pills down by about a sixth — making them 25mg — and put them into my little weekly pill case. After about three days, all I felt was a little nausea and a little spacey so I cut my next pill down by another sixth. I immediately felt the way I usually would on days when I’d forgotten to take my pill on time. I figured maybe, like the various blogs had told me, it was just a temporary drop and it would level out. It didn’t.

You wake up with a film of sweat peeling your arms from the bed. Your head is heavy and sagging with emptiness. You are a bundle of exposed wires. Every movement zaps you from your temple to your fingertips. You are seeing everything as if through a mirror. You can push yourself right up against the glass and still never touch the other side. You are sensitive. You laugh until you cry and then you hate yourself for crying. Your partner isn’t listening so you collapse to the floor in despair. Somewhere between the red pulsing in your fists and finding a clear spot on your sweater to wipe the snot, you realize how tough this withdrawal really is.

Every few days to a week, you cut back by a couple more milligrams. You go from feeling like shit to feeling dead, slowly working your way back to feeling like shit and cutting back again. This goes on for two and a half months. Two and a half months. About ten weeks. About a quarter of a year. A season. The season of withdrawal. You try to get some work done for your research assistantship when you can but it’s mostly futile. You know you’re lucky, living off the remainder of the money you earned as a teaching assistant and loans from the government. Sometimes, you’re afraid Quebec would take it all back if they looked at your file and saw how useless you were or that your langue maternelle and chosen area of study were their enemy.

D: Who are you talking to? Who is this you?

Finn: Sorry. I meant me. It wasn’t a real you. I just wanted them to feel it, if they could.

A: Do you really think that’s a good idea? People might think you’re directing them too much, and if it’s not done well enough —

D: It won’t be.

A: — if it’s not, then people might get angry or think your withdrawal wasn’t a big deal or not get it.

Finn: Ok. Yeah. I’m sorry. I’ll stick to myself. I won’t try to write for anyone else.

Anyway. After two and a half months of withdrawal — and yes, I likely went through it a lot faster than I was supposed to — after that time, I slept for what felt like weeks. I still oversleep way more than I ever did before. By the end of July, though, the withdrawal storm had mostly passed and I was excited to go back to the regular amount of depression I’d always had. I was excited for things to get a little better.

D: But things didn’t actually get better.

Finn: …No, they didn’t.

[Finn shifts. A shifts]

A: Hey, um you’ve spent a really long time on that. Maybe you should try something else. Maybe people want to hear more about how to get better. You’ve been dealing with this forever. Why don’t you give them a list of resources or something?

D: Yeah. That’d be useful, at least. Better than listening to any of us.

Finn: Ok. Yeah. I can do that. There are a couple of apps and things that have helped me over time. I’ll list a few that are easier to access, I guess.

Booster Buddy — This is an app where you emotionally check in each morning and complete a couple little self-care tasks related to whatever you’re struggling with. Doing so helps wake up your animal buddy who then thanks you and gives you motivational quotes. Also, as you complete tasks, you get points that unlock ‘levels’ that let you give your buddy cute accessories. It also keeps track of your mood, medications, and addictions if you have any. It’s a really useful and quick tool to get you in the habit of minor self-care and mood tracking.

Stop, Breathe, Think — Simple, straightforward, as-of-yet-in-my-experience not offensive or appropriative guided meditations. Select your feelings from a wide array (they separate the feelings into various categories and you can select up to five) and the app will present a series of guided meditations for you that are appropriate to whatever you’re feeling.

You Feel Like Shit — The single best interactive self-care tool I’ve ever used. This tool is made with Twine so, depending on what you’re feeling/dealing with, it will lead you on a variety of paths. It also gets you to check in on a variety of self-care things in very gentle ways — it won’t shame you if you eat poorly, for example. It very much lets you feel in control of how you care for yourself while gently nudging you to doing the most positive thing you can do for yourself at the moment, whatever that may be. I feel like it really embodies the spirit of ‘harm-reductive’ which I think is really important.

7cups — I mostly use 7cups for the growth path activities (videos, affirmations, meditations, etc.) that give you healthy reminders to help you improve what you can, as well as accepting yourself and your illnesses and being thankful for what you do have. There is also an abundance of listeners that you can talk to when you’re not doing well and community chat rooms and forums. I’ve had some awkward experiences with community members re: queerness and gender identity but overall it’s been pretty useful.

Rainymood — The sound of rain, various types of rain — it’s calming and helps you sleep.

Passionflower Valerian tea — This tea will help you calm down and help you sleep really well. Notable side effect: ridiculously vivid dreams.

St. John’s Wort & 5-HTP — If you’re not on any medication, these two supplements can be really helpful. 5-HTP is an amino acid and it’s really great for anxiety. St. John’s Wort is a plant that is basically a mild SSRI. It affects your serotonin, which is why you can’t take it if you’re already on an SSRI, because you will get serotonin syndrome and maybe die — no, really. I’m serious. That said, if you aren’t on an SSRI, this does help a bit. It might also be worth it to start taking a daily multivitamin.

(Note: I’m recommending supplements but not foods because let’s be real, if you’re depressed, you likely don’t have the energy to make healthy meals and fresh produce always rots and wilts and slimes away in that bottom back drawer of your fridge — so yeah, don’t worry, I got you.)

Also, the following songs (but also whatever works for you, you know?): “Rise Up” by Andra Day; “Keep Your Head Up” by Ben Howard; “I Wanna Get Better” by Bleachers; “Up We Go” by Lights; “Send Me On My Way” by Rusted Root; “Let the Rain” by Sara Bareilles; “Beautiful Times” by Owl City; “Thrash Unreal” by Against Me!; “Try” by P!nk; “Don’t Be So Hard On Yourself” by Jess Glynne; “Looking Up” by SafetySuit; “Make Them Gold” by CHVRCHES; “Recovery” by James Arthur; “Today Will Be Better, I Swear” by Stars.

SC: Oh! Don’t forget about your own blog, the one with all the affirmations and cute kittens and stuff!

A: No, don’t give them that. That’s too much.

R: You could but I think, for the sake of caution, you should maybe not. It’s really your decision though. Speaking of resources, how have things been going with your therapist?

A: Oh! I know this one. I was with them when they were supposed to have their last appointment. They still didn’t like him so they didn’t go to their last session because they didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings or risk an awkward dialogue.

R: That — wasn’t the best plan of action. Finn, is that true?

Finn: Yes. I’m sorry.

A: They didn’t know what to do.

SC: Ok. That’s ok. It would have been better if you had cancelled beforehand but at least now you’ll go request someone new?

Finn: I will. I promise. As soon as I have the time and energy. I just, I haven’t had many great experiences with therapists.

R: Why don’t you talk about that?

Finn: What do you mean?

R: Your experience with therapists.

Finn: Oh, ok. Which one?

R: Why don’t you start with the first one?

Finn: Ok. Let’s see.

Well, it wasn’t until age 14, between covering my clothing with safety pins and darting down halls, earphones in, crawling (in my skin), that I stumbled into therapy. A misunderstanding, really. A survey I thought was for data about teens and school and pressure that landed me in a chair facing a guidance counselor. It was my first time stewing in that silence, darkness filling with a tight-lipped pity. It was nowhere near the last.

And the Counselor says, “So you feel like you want to hurt yourself sometimes? You think about killing yourself?” So blunt, he asks, as they will all ask, even though he already has the answer in front of him. I have yet to understand the sick fascination they have with hearing you say it, hearing you say in one way or another, “Yes, Mr., I want to die.”

I dance around it, as we always dance around it, not wanting to make it a big deal, but wanting to make it maybe just big enough that maybe they’ll be able to help. So, I say, “I guess it’s more that I just want to stop being. Or sleep for a really long time.”

And the Counselor says, “Hmm,” and he nods, as they will all nod. And he will let the silence build again. As though its weight is meant to feel new. In it, I will overthink every possible way that he could be thinking about this encounter, these things I am saying. Am I a liar? Am I broken? Am I not broken enough? Am I just the lazy, never-enough bitch creature my mother always told me I am? Am I manipulating a system meant for real people with real problems?

It is the first time. There will never be a last.

This first time will lead to a call home, a referral to the children’s hospital, my mother, emotional, saying she’ll take care of it, later sternly telling me I should have come to her, me feeling guilty that I hadn’t but knowing that I couldn’t or that in so many ways I had. The first time will lead to a psychologist and an art therapy group, will lead to more silence, not opening up, my mother telling me I’m wasting her money if I’m not speaking one day, telling me not to air our dirty laundry or that it’s all my own fault the next. This will lead to me skipping psych appointments, will lead to more guilt, will lead to more skipping — of school, of social gatherings, of existence, will lead to my extensive knowledge of home decor and home improvement from watching HGTV all day every day laying on the couch, will lead to me scraping my way out of high school. These will lead to more therapists, more skipping out on therapists, and so on.

When I got to university, I never tried to register myself as mentally ill with the center for students with disabilities. I wonder if anyone ever does. Or do you all feel that same complicated dissonance between the fear that the university won’t see your disorder as valid, that maybe they’ll see it as too much, or feeling like maybe it really isn’t valid enough?

[A shifts and starts picking at the skin of their cuticles. D yawns.]

I don’t know. This one doesn’t quite feel right either.

SC: Are you sure?

[Finn nods.]

R: Ok. Were there any other ideas that you had?

Finn: I mean, I thought about looking at one of those posts about ‘habits of happy people’

R: Ok. Maybe try that?

Finn: Ok. I’ve gotta get one though.

Ok. Got one. Here goes.

The energy it takes just to do taxes is enough to warrant a week of sleep. Keeping Busy may be a distraction but depression is, by definition, lying in bed at 3 pm watching Parks & Rec, hearing the pigeons in the heat, wanting to throw rocks at them, not having the energy, looking at the mountainous terrain of dirty clothes on your floor, the smell of gelatinous tea in mugs, and rolling back over. Depression is not doing the thing until the thing must be done because there is never the energy. Depression can’t make itself busy. Depression is always rushed.

2. Have five close relationships. National surveys find that when someone claims to have five or more friends with whom they can discuss important problems, they are 60% more likely to say they are ‘very happy’

They say. They say like it’s easy, like it’s easy to keep in touch when there are a million other responsibilities you already don’t have the energy for; like they don’t have a voice telling them they’re unworthy, they’re boring, they don’t deserve friends, they’re just annoying; like isolation isn’t the default; like they don’t feel like the longer you wait, the more the anxiety tells you not to bother, the more each unanswered message and cancelled plan makes you feel broken. Ignore it, they say. Do it, do it anyway, they say, no matter how alone you feel regardless. Do it. Then you, too, can be very happy.

3. Exercise. Endorphins, endorphins, endorphins.

Yes, more to ignore. Ignore the inability to get up in the first place. Ignore the exhaustion. Ignore that it takes an hour to look a way you don’t hate and ignore the anxiety of how the exercise will make you look by the end. Ignore the anxiety of exercise in general, of doing it around folks, of not doing it right, ignore the energy spent doing it. Ignore it. Endorphins will solve everything.

4. Spend more money on experiences. Trips! Shows! Doing, not having!

Ignore the correlation between poverty and mental illness. Ignore the fact that we — that I — cannot afford experiences, do not have the luxury to plan such things, to purchase more than the necessity. Ignore the ease of retail therapy on the rare occasion, that less effort can be put in and one comes out with a reusable item that makes them feel good. Ignore the energy it takes to plan trips, the social investment necessary to see shows, and the energy that takes. But most importantly, ignore poverty, ignore it —

D: I don’t think that’s elaborate enough for people to care. There’s no story there.

A: Yeah, I’m not too sure about it, either.

D: You’re not even trying.

Finn: Well, what do you want? There’s no story in any of it. None of them. They’re bits and they’re pieces. They’re not pretty. I’m not articulate. I’m not Plath. My fig tree has been in front of me for years and all the figs have already swollen and fallen and died. I am what I am. I get up every day. Or I don’t. But I try. And I worry. All the time. About everything. This has been my life, my whole life. I am trying to get better but I’m not there yet and I don’t think I ever will be. So, what do they want from me? It’s something that just isn’t there. They want beauty in melancholy. They want that thread of creativity only visible to those who suffer. But I can’t give them that. I don’t have the energy for that. Don’t they see the paradox? Write. About mental illness. As if that could really happen. And how? Where do I even start? Where do they want me to end? It doesn’t end. The silver linings are shards that will come back and slice you up if you don’t hold them carefully. If you rest on them, if you lean the whole story into them, they will shatter and you will bleed. Do you want to bleed?

SC: I’m so sorry, Finn. Why don’t you tell them about what you’ve been doing this past year? What happened after the withdrawal, where you are now?

Finn: This past year? What am I supposed to say? After I went through withdrawal, I took a vacation with my then-partner to the town my grandmother grew up in, the town where I spent all my summers growing up. It was hell. I hadn’t been there in years and I hadn’t realized how oppressive it would be. I mean, I shouldn’t have expected a town of a couple hundred people to respect my pronouns or my visibly queer and interracial relationship, but for some reason I did and I was trapped; Joon was even more trapped. Then, right before the new semester began, my deadbeat dad up and died. Hey, haven’t seen you in ten years but bye forever, here’s tens of thousands of dollars in debt from my coke habit. Have fun with that messy grief and the lengthy, costly legal processes of renouncing succession. And in the midst of that, I started to stand up for myself around my mother, which led to more guilt and gaslighting until I realized I may not be able to have a relationship with her anymore. Then, on New Year’s Day, Joon left me. There were real problems there and I respect that, but it didn’t make it any easier, especially when I found out how immediately (overlap likely) they started dating The Australian. Basically, this last year was hell and I hit the lowest low I’ve yet to hit. And yes, it was around that point, in January, no friends, no family, no nothing, that I realized I needed to just kill myself or dedicate myself to getting better. There was nothing else left.

So I chose to get better. I chose to start contacting people, meditating, learning how to be grateful. I am getting better because I keep trying. But it doesn’t mean I don’t still fall behind, fall apart, and isolate like all hell. It doesn’t even mean that I get up at a regular hour. Half the time, the only things I can list in my gratitude journal are, “I am grateful for the sun. I am grateful I am here.” I am still depressed and I will likely always be depressed. I’m just trying is all. But it’s hard. It’s not a happy ending by any means because it isn’t the end and there will never be an end.

D: Ugh. Now, you’re just monologuing.

Finn: Well, yeah. That’s what I’ve been doing the whole time, isn’t it?

Epilogue [of sorts]

D [Depression]: I guess. That wasn’t very inventive, though. You’re not very good at this, are you?

A [Anxiety]: Are you sure you want to tell them that? Isn’t it better if they find out on their own? Oh, but then again what if they didn’t get it at all. Maybe you should start over. What if they think you’re extra weird for talking to yourself? Can you make it clearer that these are all just things you say to yourself? That you haven’t actually fractured your mind this way? Wait. Did I do it? Is that enough?

R [Reason]: It is what it is. One way or another, you produced something.

You completed the task and that’s enough.

SC [Self-Care]: You did. It doesn’t have to be perfect. The point is that you got it done and you were able to speak, no matter how many times the others interrupted you. You are brilliant. You will keep going. All of us are learning and we are working together to help you. You are helping you. Keep pulling yourself out. Stop when you have to. Rest. But keep going. Keep going. Keep going. You’ve got this.

Finn [Me]: Thanks, I guess. At least it’s a start.

these words by Finn Purcell were inspired by the colour of Owen Gent

TW: Self-harm

The feeling that precedes it is a quiet panic: the sense that she is not feeling enough, or feeling too much the wrong way.

Safety pins and tacks do the job sometimes. The marks they leave are an irritated red. They heal like cat scratches, but too straight to fit the lie. It takes a lot of pressure to draw blood.

Sometimes, she can stave off the urge with the drag of her thumbnail down her forearm, or the center of her throat. This leaves a mark, too, but it’s faint enough that people don’t ask.

Sometimes other people’s bodies will do the job. His fingers are clumsy, floundering. She wakes up in a panic the next morning when she remembers what she’s done but not what his name is. She regains the knowledge via text from a friend: Hudson, like the Bay.

His fingers are slick when he enters her. He puts them in his mouth and sucks on them first, maintaining eye contact the entire time. His fingers jab into her in the general direction of where they both assume her g-spot is. They are rigid and insistent, maintaining the ruthless pace of a second-hand jackhammer.

Metal is different. When she uses scissors — knives and razors seem too dangerous — she expects to see the flesh part red and wet, revealing complex patterns inside, like a pomegranate, or the little teardrops inside an orange slice.

(She looks them up later: they are called vesicles. She repeats the word to herself: vesicles.)

Instead, there is just blood. Not a lot of blood. She thinks there are some major veins on the inside of your thighs or something; she keeps this in mind when she drags the scissor blade over the muscle there, flinching. The metal is not the problem: it is her own wavering grip, too afraid to push too deep, of blooming more pain than she’s bargained for. She knows people have cut through muscles down to the bone. She knows people who have ended up in the hospital for it. She knows she is supposed to feel comforted that she’s not part of this dysfunctional elite, but mostly the knowledge makes her feel like she’s not trying hard enough.

She tries to keep them even in length and depth. They never are. The blood pools in straight lines. She wipes it away; it blossoms again, a thin line interrupted by sluggish beads, a delicate filament made of nothing but her.

When she was little, she always ran her baths too hot. She would sit on the edge, naked flesh pricked with goosebumps, running cold water in and stirring it, flinching at the hot current that made her hand flush. She acclimatized to heat in increments, trained herself over time to embrace water that makes her feel raw all over, makes her body breathe plumes of steam when she rises.

these words by Caitlyn Spencer were inspired by the colour of Owen Gent

The man beside me asks, “Business or pleasure?” When I don’t reply, he laughs and tells me I need to relax. I don’t know how to relax, so I open the in-flight magazine. I hope this is a good way to end a conversation.

these words by Sarah Christina Brown were inspired by the art of Tran Nguyen

curating colour requires

knighthood, rescuing a coloured image

restoring it to a coloured name

in the woods there is more than colour

the texture of bark, bitter acrylics

the labour beneath

the layers

if an idea is painted, a history, a desire

a colour is not just a colour

orange is not colour

merely

it is instinct, fang, rupture

awakening

a devouring (of roots)

of tigerhood

flesh open skin peeled back

slow and half at ease

the bones remain

uttering a different story

the pain is a ghost language

*

once upon a time

I came I saw I assimilated

trapped in the woods

I use white words, leaving a trail

of crumbs in circular argument

I write I grieve I love

in

more than

colour

but wielding a sword in white space

is easier

than cutting down

bark

these words by Lily Chang were inspired by the colour of Tran Nguyen

“Crusading”

word by Jacob Goldberg

colour by Loish

Elias’ bag of chips had gone missing. He was walking around the classroom searching for his bag of chips. He brandished his lunch box at Mr. Epplin, telling him that they were there this morning. He asked Mr. Epplin where they had gone. Meanwhile Mr. Epplin hadn’t even asked him a question. He had been standing at the chalkboard writing the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus. And he looked to everyone to be terribly confused, like someone who had just been told that in fact Santa did exist. Elias didn’t care. He wanted to know where was his bag of chips. LAYS. Bag made of 70% reusable goods. The bag doesn’t mention where the last 30% came from. Elias speculates that it came from non-reusable goods. This is what Mr. Epplin calls an educated guess.

Several minutes had elapsed since class began but this class seemed to be a lost cause. Of course, it could be have been recovered, had Mr. Epplin had ambitions to resume. But he didn’t. Mr. Epplin was looking for Elias’ chips. In fact, everyone was. Elias had corralled all of his classmates and his teacher into searching for his chips.

Elias asked every one of his classmates to empty their bags on their desks. He asked them to examine their belongings for his chips. He told them that they might have forgotten what you put in their bags. Sometimes, Elias said, he could overhear Mom whisper to Dad at Olive Garden that she’d forgotten something and now there was in issue underneath the table. This issue was her period. But dad would find a tampon in her purse. Elias said that the moral of the story was that you sometimes forget what you put in your bag.

Mr. Epplin totally understood what Elias was getting at. He exclaimed to the class that he would be their father and inspect their bags for them. One girl, Eve, wondered whether this proclamation was grounds for terminating Mr. Epplin’s career as a teacher, but God intervened. He said to her, “Your namesake ate the apple: Don’t be the second Eve to fuck it up.” She wasn’t sure how to take this advice.

When Ms. Chu, the biology teacher, appeared at the door with her students, Mr. Epplin, frisking Joseph, told her that he could arrest her if he wanted. He removed a pair of handcuffs from his breast-pocket and said don’t test me.

Elias had removed the axe from the In-Case-Of-Emergency box and began to hack at the room’s infrastructure. One student had removed a wok from his backpack, another dry ice. Several students in the room were smoking cigarettes. Ms. Chu asked a student for one. The student said no. Ms. Chu and Mr. Epplin were holding hands. There was much excitement. Yes. Yes yes yes.

With the floorboards uprooted, the desks overturned, the windows kristallnachted, and the wallpaper peeled, Elias sadly decided that his chips were not in the room.

The next step was to set off the fire alarm. Elias’ thinking was: chips are denser than water, so they’ll sink in the rising water. Yes, Ms. Chu, the science teacher agreed. They emerged from the classroom, all attached to toddler leash.

The day would end soon, and Elias would go home hungry and chipless. All of Wilmington High would soon be on the Crusade for the Chips. Here, there is separateness in the togetherness, loneliness in the community. This crowd grows, and they are not alone, warding day and death away.

“I was thinking about what it means to be a member of a group, to be driven by an idea, buying stuff, and how advertising can compel us to do things. The girl in the picture seems like she could inspire such a crowd.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.