so we took up inspired

fights like the -isms,

the air, the water,

the rolling glaciers,

the fears we feel

in homes, our least conversated

doors staying owned,

most only accepting MEN, to say (like anyone intelligent asked or cared)

they still exist

to pretend they wouldn’t jerk a man off in a secret vacuum.

The glow of a few decades’ mistakes

still spreads red,

despite us being in charge forever and no one else, no handed down way, no alien us,

most mostly

alike, tho some stopped reading this poem

because of my science on men wanting to try cock at least once,

my science being don’t make an individual

a video of that same individual being you. They are not you.

This is where we’re at.

No gigantic man handing us down to us. I can’t stress that

or anything else enough. I am shaking for a world of reasons.

We have a 2000 problem, 0000’s of MEN

are videos displaying how dim men continue

to study spectrum

with the light out.

That last bit was a metaphor

for porn, men’s rights, and the new Nazis

(you lost fucks see me on George Street, stab fast,

or you’ll lose the personal war too this time);

this open bomb of a world.

Amazing we exist in this at all. Amazing we exist.

Amazing.

The young man at the protest about to climb the lamp

can’t be Gene Kelly,

trained to keep his hands off the high light,

take home as much grace as he can scrape off the bottom.

There is a baby who is important to the future lying

by the political blast zone Schrodingering,

and because everyday’s a news day, the knife

or branch in your hand;

keep the future you don’t know down is the red lesson. Stab a gay baby.

You have to have a gun,

your right to not much isn’t God

given, or taken. It’s plain. Your belief is a ladder to another finity.

In charge of nothing

but fixing

the world we went into

debt to see, and have

since brunched back

to our mothers and fathers,

lived inside basements, inheritances,

until we had the wall space to hang

what failed us; photos of hairdos all

ecstatic to be sepia, cross-legged on the wall, denying they’re putting us down;

every memory back then

straight.

Oh mother,

come back to bread.

Yes, we are furious,

because we were ushered in, without shushing, when the world was still

blind, and quarrelling over how much YES is left when it’s a ruin, and the whole

time just around the corner

You, absolutely

not your father,

maybe President;

worth a shot-

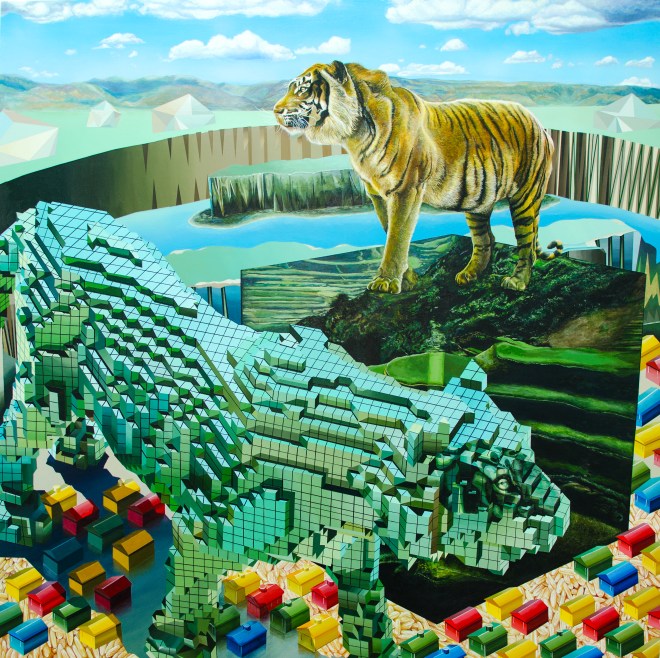

these words by Justin Million were inspired by the photography of Alison Scarpulla

You must be logged in to post a comment.