I was fifteen years old when she told me for the first time. I had asked her how she was doing. She looked squarely into my eyes, which look exactly like hers, and said words that she would go on to repeat many times: “I am waiting to die.” She said it in her usual way: tired yet hard and brazen. No tremble, no sadness. Defiant eyes. She didn’t say it to complain, or to illicit pity. (Though that’s what the others sometimes said about her.)

Most grandchildren don’t expect to hear that kind of language. Not me. I was fairly certain I knew why she said it. I knew about the angry welts on her body from his hands. I had been there once as a small child when he grabbed her by the hair and smashed her head toward the corner of the wooden cabinet. It was the last thing I saw before she pushed me out of the room and closed the door with her falling weight. I knew that she had been the sole breadwinner her whole life, working manual labour to put food on the table, to pay for her children’s school fees, to unwillingly fund his addictions to gambling and prostitutes, cigarettes and alcohol. (This later came to include funding his child support payments for those illegitimate children that we didn’t talk about but whose mouths were also fed by her hard work.) These, after all, had been the constant realities of my life as I flitted in and out of their home, not quite innocent enough to escape their burning silences but thankfully spared from the fits of rage and violence that I knew existed underneath. But I still had to ask her “Why?” to hear it from her own lips.

“Because my health is clearly worse than his, and at this rate, the only way I will find peace away from him is when I’m gone.” She was in her mid-seventies at this point.

“But if what you want is to be free of him, isn’t there anything we can do other than wait? Can’t you get a divorce? Can’t you move out and stop living with him?” I asked. Visions of my grandmother as I had never known her, happy and carefree, danced before me.

“There’s no point.” She seemed instantly to regret saying anything, shooing away my questions and telling me that I wouldn’t – couldn’t – understand. There was too much I didn’t know. In my teenage mind, I felt patronized. What was she keeping from me?

I asked my mother. I asked my aunts. I got mixed responses. From “We’ve tried. We’ve offered multiple times to move her out, but she won’t leave. And he won’t leave either,” to the more frightening, “She’s past the point of moving on. There’s nothing you can do for her now.” I felt impotent. I thought about those defiant eyes; that hard stare that she gave him when she wordlessly served him his breakfast, lunch and supper which she cooked from scratch, no matter how bedridden the doctors told her she was. Diabetes, hypertension, a heart attack: nothing could stop her from keeping him fed. It seemed impossible to understand – if she wanted it to end, why didn’t she just walk away?

Ten years have passed since she first declared to me that she was waiting to die. Her body is older, closer to the relief she seeks and further from us who love her. On a warm January morning this year, she told me yet again, “My bones are very tired. I am waiting to die.” And for once, finally, she was ready to say why.

“My father had wanted to choose a husband for me, as was common in those days, but I was headstrong and insisted on marrying your grandfather out of love. We had known each other since we were children; we grew up as neighbours. My father relented and we got married. The first couple years were okay. We had your aunt and your mother. But then, things started changing even before your uncle and aunt were born. You know already: gambling , alcohol, prostitutes. I had to start working, and then I had to work more and more. We were getting poorer and poorer…at some points we were barely eating, and we had to pull your aunt out of school. My father tried to loan us money but your grandfather always spent it all. Since I’m a woman, my father couldn’t trust me with money…he always gave the loans directly to your grandfather. But it was always gone before it ever reached me or the children, and I could never pay my father back, no matter how hard I worked. I could barely put food on the table with my salary. He eventually had to cut us off because he realized that any cent he loaned us would be a cent wasted. He passed away before I could ever pay him back, before I could ever apologize for costing him so much and for having wronged him so greatly with my choice of husband.”

Before I could say a word, she continued.

“My mother was much more sympathetic. She moved in with us to care for your mother and her siblings so that I could work more hours. Sometimes, I would have to go away for days at a time. She always begged me not to go for too long.”

Tears were falling down her cheeks.

“One day, your great-grandmother got sick while I was gone. She must have been in her late 70s and she was such a tiny, frail person. Your aunt took her to the doctor’s, where they diagnosed her…”

The tears came stronger; her words almost a whisper.

“With an infection that came from untreated chlamydia. Your aunt had to translate the doctor’s questions as to how on earth a woman at that age could have contracted…”

She paused. The realization dawned on me.

“…a venereal disease. And that’s how I found out that he had been raping my own mother for nearly twenty years.”

She took a pause. We blew our noses, and wiped our tears.

“She said she never told me because he threatened her by saying that if she ever told, he would hurt me and the girls. Of course, by that point he already had… your aunt and uncle were forced onto me by assault. I didn’t want to have any more children after your mother was born. And my little girls… I could only protect them when I was home, but when I wasn’t around…Your mother was seven years old when she came crying to me when I got back from work. She said she had been bent over, feeding the chickens when he came over and…and…”

She couldn’t finish.

“He used to break broomstick handles over your mother’s head for her insolence. But she always fought back. Not like your great-grandmother. She was so tiny, so meek…I can never forgive myself for any of it.”

My ears felt like they were ringing, my chest felt heavy, my eyes were stinging. Three generations of women before me had been abused by the man who was sitting on the other side of the house…

Except that he wasn’t. He wasn’t on the other side of the house. Somehow, in all our sadness, we had missed the sound of his footsteps approaching. He was suddenly standing there, in the doorway looking silently at our puffy eyes and runny noses.

and runny noses.

As our eyes met, he said, “Did you read the news about the EU?”

I was incapable of saying a word. I wanted to get up and punch him in the face. I wanted to lash out and scream at him. I wanted to push him down the stairs, out of the house and away from all the people that I loved.

I looked at my grandmother. The defiant eyes were gone. She did not look scared of him: she looked scared of me. She gave an almost imperceptible shake of the head as if to say “Don’t.” I thought I understood. He had already ruined everything that was sacred to her…her mother, her father, her children, herself. If I said anything, he would be on her as soon as I left. I kept my mouth shut. Once he had crossed to the living room, she whispered that I must promise to never never breathe a word to him about it. I promised, frightened of what he would do to her.

I spent much of the next twenty four hours horrified. I tried to convince her that we needed to make a plan to get her away from him. She was infuriated by my many suggestions.

“You promised me you wouldn’t make a fuss!”

When it was clear that I wasn’t intending on giving up, she took me aside and looked me in the eye.

“I’m not afraid of your grandfather. He can do nothing worse than what he has already done. So stop trying to ruin everything. I was foolish to think that you would ever understand.”

I was so confused. I had thought that she didn’t want me to say anything precisely because she was afraid of the violence he might cause.

It has taken me a long time for me to understand why she hasn’t left. I see now that my grandmother has had very few choices in her life…but her choice to stay or leave is hers to make, not mine to make for her. So much has already been taken from her. Who am I to take away her one last choice to solemnly await death? She has decided for herself that while on earth she cannot escape the madness and guilt of his doing. No physical distance from him can set her free from her anger towards herself. She seems to choose to be within hating distance of him so as to concentrate all her silent fury outward, instead of in. As much as she hates him, I feel she hates herself more for not having been able to stop him. She comes from a generation that doesn’t believe in counselling, so I have no way to help her shed her guilt. Instead, she waits for the end.

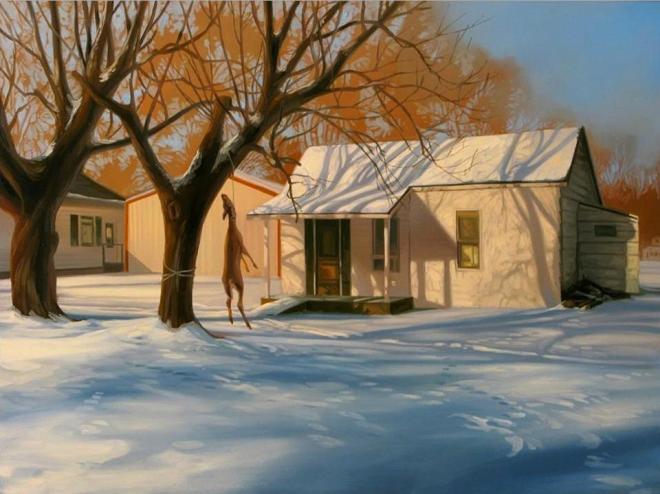

these words by Jo-Ann Zhou were inspired by the colour of Raphael Varona

these words by Jo-Ann Zhou were inspired by the colour of Raphael Varona

SHARE this collaboration!

You must be logged in to post a comment.